America’s Centennnial Year: 1876 was a time of booming fortunes, and New York was bursting with post-Reconstruction fervor, the metropolis burgeoning, robber barons feeling their oats. Thriving since the Civil War’s onset as a manufacturer’s paradise, the New York region’s many tentacled rail system and giant natural harbor fostered a cornucopia for commerce of all sorts. Wall Street remained the office work hub of the City’s financial commerce, be it stock-jobbing, cotton trading, money-lending or the like, but “uptown,” along Broadway, wholesale trades of all kinds waxed greater and greater. Immense cast iron loft buildings sprouted along Broadway and side streets like Mercer and Greene, north and south of Canal Street. 450 Broadway was one such Centennial palace of commerce, one of the hundreds of structures designed by John Snook (1815-1901) during his lengthy career.

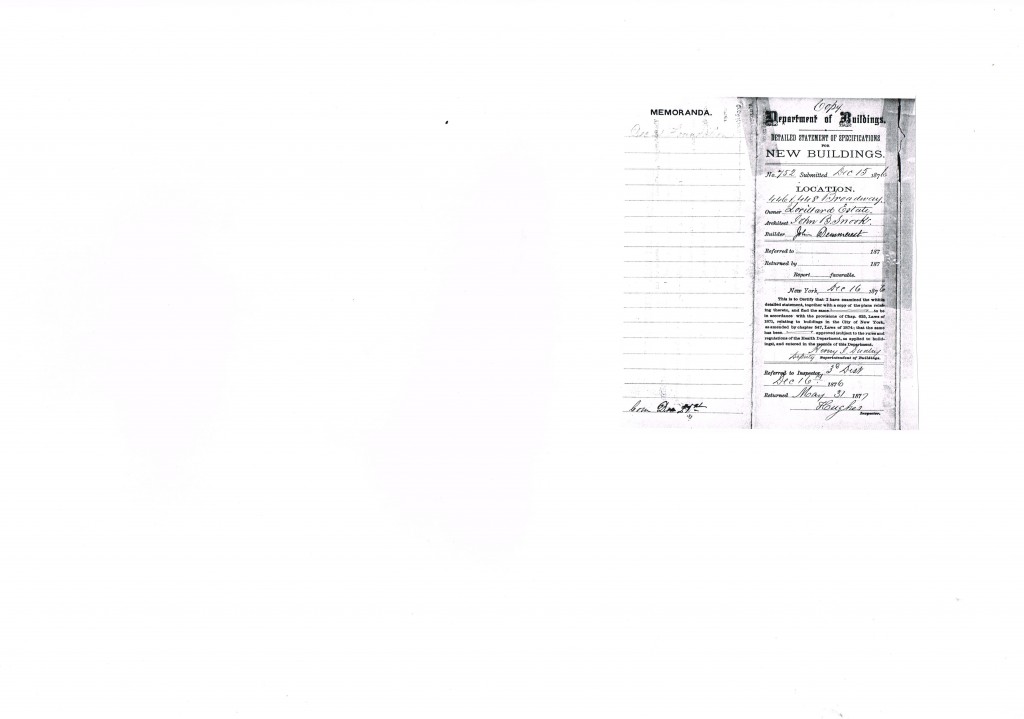

Hardly as well known as the designer’s Grand Central Depot or his Metropolitan Hotel, 450 Broadway (listed in the New Building Application for a pair of similar structures then known as 446-8 Broadway) was a utilitarian project. Snook, whose offices were then at 12 Chambers Street, designed the buildings for the Lorillard Estate.

450 Broadway is a survivor, a holdout: the majority of its tenants still in the shmate business one way or another, its main tenant, Bettertex selling drapery and upholstery fabrics at rates undoubtedly a fraction of what one finds at 57th and Third…The sad sack building is easy to penetrate: no concierge at a fancy granite-topped desk greets you with a suspicious smile as you pass through its dilapidated entry doors. Astonished when I encountered it, I crept up the sloping wooden stairs, past the peeling paint on the battered wainscoting, eyeing the ancient gas cocks and drifting back into the days when Broadway was be-teemed with horse shit and mud, and chaos of wagons and draymen’s cries filled the air. Scores of immigrant seamstresses and tailors filled each floor, working 12 hour days for pittances to support their broods. Neighborhood saloons did a brisk business after a shift ended. Hard labor and cheap beer filled the days and lightened the nights.

450 Broadway, whose construction commenced four days before Christmas, 1876, sat on a 6000 square foot lot with 50 feet of frontage on Broadway, with 20” thick walls on the first story and 16” on the upper stories, decreasing to 12” on the fifth (top) floor. Cast iron fabricated by the renowned Cornell workshop of was employed on the façade, as with so many commercial structures in the neighborhood. According the 1973 designation report for the Soho Cast Iron Historic District issued by the New York City Landmarks Commission (http://www.nyc.gov/html/lpc/downloads/pdf/reports/SoHo_HD.pdf )

“Nos. 446-448 and 450 were built at the same time by J.. B. Snook for the LoriIIard Estate and. share a common facade. Both are five stories high; No. 446-448 is six bays wide and No. 450 is three bays wide. Quoined pilasters flank the ends of each building and form a dividing line between the two sections. Columns topped by Corinthian capitals define the window bays and the ground floor openings. A simple undecorated cornice divides each of the floors. The main entablature adds an appropriately strong accent to the composition of the joint facade. Flanked by large console brackets, each topped by a sort of neo-Grec terminal block, the cornice of each building stretches above a paneled concave frieze. Additional, concave brackets with their own incised terminal blocks alternate with the panels on the frieze. These non-traditional decorative

details combine with the other, elements of the buildings to form a handsome open classical composition.” The structures were completed in six months.

The streets between Canal and Houston declined hand in hand with the decline of warehousing and manufacturing in lower Manhattan, slowly strangling to death after World War I as the development of more efficient transportation options and modern structures took place outside of the core of New York. By the close of World War II, what we now know as Soho was a half-wasteland of semi-vacant, almost century-old, obsolete loft buildings, its streets accommodating a sorry fraction of the pedestrians and commercial traffic that clogged the neighborhood in 1918. Though the ground floors of most buildings remained occupied with some sort of commercial activity, upper floors went dark, and were rented to artists, with no amenities and few utilities while Robert Moses planned the evisceration of the island with his planned but ultimately doomed Lower Manhattan Expressway, finally abandoned in 1962: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lower_Manhattan_Expressway

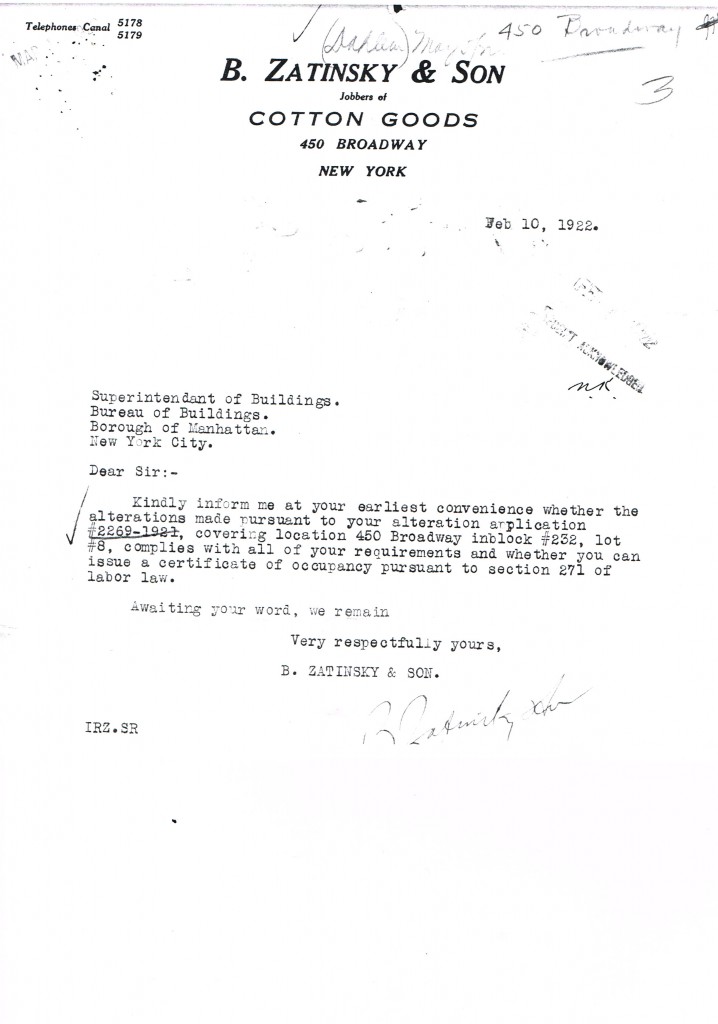

A single elevator shaft was installed in 450 Broadway in 1899 at the front of the building, and fire escapes and improved interior fire egress installed in 1917. That same, now decrepit lift services 450 to this day. In 1927, the upper floors of 450 Broadway were in all likelihood still primarily occupied by secondary manufactories in the needle trades. “B. Zatinsky & Son, Jobbers of Cotton Goods” occupied space at 450 in 1922 and pressed the owner to provide evidence of legal compliance of the structure with the New York State Labor Law. Though the outcome of that interaction is unclear, by 1941, the use of the upper floors of 450 Broadway had downgraded to storage lofts, which undoubtedly had less stringent code requirements than factory uses where workers’ health and safety issues were stronger.

The Garment District, as we call the area today west and north of Herald Square, reached the peak of its rapid construction by the onset of the Great Depression, and much of the clothing manufacturing and fabric jobbing moved uptown to more spacious and modern buildings, exacerbating the downward spiral of the Canal Street neighborhood. Even with the disappearance of garment factories from the neighborhood before World War II, some fabric wholesalers remained clustered around the corner of Broadway and Canal Street well into the 1980s.

How fervently I hope and ardently I pray for the health and welfare of Bettertex and Weisenfeld Textiles at 450 Broadway, even though Mr. Weisenfeld apparently harassed one of his residential loft tenants for years after a 1981 fire made the fifth floor uninhabitable. The Owen family had claimed to have lived on that floor since 1969, a typical “Soho” use as the decrepit structures started to welcome residential tenants into otherwise unrentable spaces in the 60s.

I won’t pass judgment on the merits of the plaintiff’s claim:

(See: archive.citylaw.org/loft/arch1997/Lbo-2081.doc )

Truth be told, I do not care, though: whether by intention of mere sloth, some structures in this great city are left alone, even to rot. 450 Broadway is a treasure, as much so as any “restored” jewel of Soho or the Ladies Mile, for in its shabby decrepitude one can better grasp the rich history hidden in its walls. Best to go see it soon. In the blink of an eye some condo developer will get his mitts on it and all will be lost to Mammon once more.